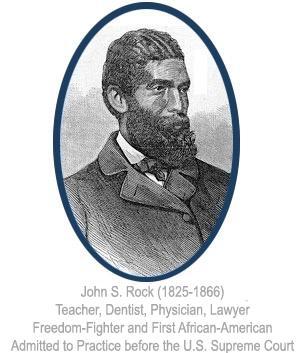

John Rock Biography

"And today the whole civilized world acknowledges that the Abolitionists have been right, and that justice must prevail." John S. Rock, January 16, 1863

In 1856 as America drew ever closer to civil war, the U.S. Supreme Court, the highest court in the nation, issued a decision in the case of Dred Scott v. Sanford that "Any person descended from black Africans, whether slave or free, is not a citizen of the United States, according to the Declaration of Independence," a ruling which, in effect, denied slaves any claim to freedom and any African-American the rights of citizenship. Four years later, John Rock; American teacher, doctor, dentist, lawyer, abolitionist, and civil rights leader; argued that "human rights are not a property of the skin, but an attribute of the soul," and that "the sublime principles laid down in the Declaration of Independence are sterling truths and not 'glittering generalities'."(March 2, 1860, Liberator.)

John S. Rock was born on October 13, 1825 in Salem, New Jersey, a small town near Wilmington, Delaware. His parents were free northern blacks, and though they were of modest means, they encouraged Rock to learn and pursue his education in a time when few children finished grammar school and when it was illegal in many states for African Americans to learn to read. When Rock was not yet 20 years old, he took a teaching position at a one-room schoolhouse in Salem and though he enjoyed the work, he desired more. For four years, Rock read medical books and apprenticed with two doctors, Dr. Shaw and Dr. Gibson, often for eight hours a day after teaching, to prepare himself for medical school. Because he was black, however, no medical school would admit him and he instead turned his attention to dentistry.

In 1849, after a year of apprenticing with a local dentist, Rock decided to establish his own practice in Philadelphia which had one of the largest populations of free blacks in the country. Though he displayed great skill as a dentist, his patients often could not afford to pay and Rock could not support himself financially in this profession. Rock renewed his interest in medical school and in 1852, with the help of white doctors who supported his cause, he was allowed to enroll in the American Medical College of Philadelphia. Because of his dedication and his tremendous intellectual skill, he earned his medical degree in only one year, and soon moved to Boston to open a medical and dental office.

Boston, at this time, was one of the centers of the abolitionist movement, and Rock soon became involved in its efforts by giving speeches on racial issues. He quickly earned a reputation as a powerful and persuasive public speaker. Once his medical profession was well established, he dedicated nearly all of his time that was not focused on medicine to speaking out against slavery. He traveled across New England to deliver speeches with other influential abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass who argued "Where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property be safe."

Rock's health began to fail in the mid-1850s, probably due to the effects of tuberculosis, and his condition continued to deteriorate until, in 1857, he was forced to give up his medical practice. He believed that he could find more advanced care in France, but U.S. Secretary of State Lewis Cass denied his application for a federal passport claiming that a passport is evidence of citizenship, which, as the Dred Scott case made clear, was not an entitlement granted to African Americans. Rock and other activists were outraged at this ruling. Rock was finally able to obtain a passport from the Massachusetts Secretary of State, but the bitter resentment he felt over this injustice would not subside.

Rock remained in France for eight months recovering from his illness during which time he studied German and French. When he returned to the U.S., he continued his abolitionist activities with new fervor and linguistic abilities. His deepest commitment was to justice for his race, and now, no longer practicing medicine, he began to study law. In 1861, Rock passed the State of Massachusetts bar and almost immediately thereafter was appointed by the governor and Boston city council to be the justice of the peace in Boston and Suffolk County. He also opened a law office on Boston's famed Tremont Street where he challenged the laws that denied African Americans equal rights and full citizenship.

In his speeches, Rock denounced the government arguing that "American liberty has always been a name without meaning, a shadow without substance...," but in January 1863, he had cause to rejoice when President Abraham Lincoln issued the emancipation proclamation, which represented a major step toward the ultimate abolition of slavery in the United States and a "new birth of freedom." Rock delivered a moving speech to a cheering crowd, declaring:

This is a great day, and we have passed through a great year in the history of my race in this country. In one short year, the gain on the side of freedom has been immense. Among the great events, we are reminded that the entire national territory has been consecrated to freedom; the national capital has been purged of slavery; it is decided that a colored man is a citizen of the United States; a quarter of a million slaves have been liberated by the war; and to-day, by the military power vested in the President of the United States, he has declared FOREVER FREE three million slaves!

In the last years of his life, Rock set out to accomplish one more landmark achievement. Justice had been a cause that he had long championed, and he wanted now to gain admittance to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court, the highest judicial authority. In his way stood Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, the judge who had ruled against the citizenship rights of African Americans in the Dred Scott case. In 1864, Taney died, and a door opened for Rock to appeal to the new Chief Justice, Salmon P. Chase, an antislavery advocate. On February 1, 1865, Senator Charles Sumner petitioned the court on Rock's behalf stating simply "May it please the Court, I move that John S. Rock, a member of the Supreme Court of the State of Massachusetts, be admitted to practice as a member of this Court." A reporter for the New York Tribune later described the event thus: "The grave to bury the Dred Scott decision was in that one sentence dug; and it yawned there, wide open, under the very eyes of some of the Judges who had participated in the judicial crime against Democracy and humanity."

After being admitted to the Supreme Court, Rock was received by the U.S. House of Representatives, the first African American to do so. His health continued to worsen, though, and he died of consumption in Boston on December 3, 1866 having never argued a case before the U.S. Supreme Court. His belief in the dignity and rights of all Americans and his long fight for justice had set a great legal precedent, however. Before the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, he had obtained one of the most highly prestigious symbols of citizenship and he had paved the way for all African Americans to become active and equal participants in the governing of the nation.

Click the following wording to return to the NWCU Essay Contest page: Annual Northwestern California University Essay Competition